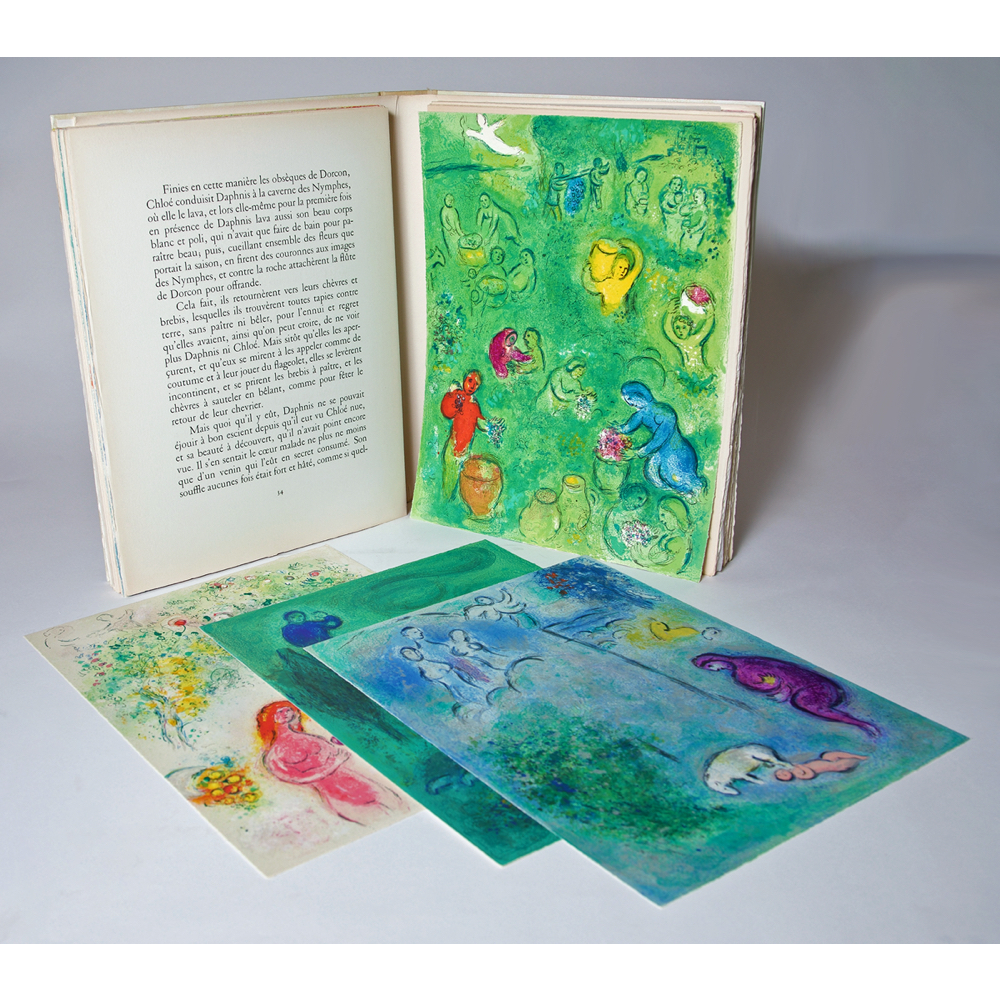

Longus. Daphnis et Chloé, illustrated by Marc Chagall. 1961, Éd. Tériade, Paris

1) What is an illustrated book?

This is how 20th-century painter, illustrator, typographer, printer and art publisher Pierre-André-Benoît (PAB) defined the illustrated book:

“A book, or even in some cases a book-object, published/created in a limited number of copies, or even in a single edition, very often produced by hand and generally distributed outside traditional distribution channels, often even by the author himself”.

We couldn’t define him more precisely than this art publisher who worked with Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró, Jean Dubuffet and others.

Although illustrated books have been in print since the end of the 15th century, when engraving was invented, we’ll be looking at the works of the late 19th and 20th centuries to which the above definition refers, as they took on a particular twist at that time.

In fact, the 1870s heralded the golden age of illustrators’ books. Luxury editions proliferated alongside mass-market editions. It is generally accepted that illustrated books took a new direction when famous painters were called upon, rather than master engravers, to accompany stories or poems in pictures. The first of this kind is an 1875 edition of Edgar Poe’s poem The Raven, translated by Stéphane Mallarmé and illustrated by Edouard Manet. Comprising four large engravings, plus the bird’s head on the cover and its silhouette on the bookplate, the painter’s productions extend the poem’s imagination to form a new art object in its own right.

From the Second World War onwards, art publishers allowed even more freedom in artistic experimentation, and it was now often the text that submitted to the prints, rather than the other way round.

Jazz, illustrated and written by Henri Matisse, is a major work in the genre known as livre d’artiste. Commissioned by the famous publisher Tériade, the painter worked between 1943 and 1947 to create and produce 20 stencil plates based on the artist’s collages and cut-outs. But for these works to constitute a book, it was necessary to produce written material to complement the stencils. Henri Matisse therefore provided Tériade with sixteen short texts that were “remarks, notes taken in the course of [his] existence as a painter”. Thus, the heart of Jazz is the work on chromatic arrangement and cut-out shapes, and everything is done to highlight the prints, the text being secondary.

“The exceptional dimension of the writing seems to me obligatory to be in decorative relationship with the character of the color plates. These pages therefore serve only to accompany my colors, as asters help in the composition of a bouquet of flowers of greater importance.

THEIR ROLE IS PURELY SPECTACULAR”.

2) Des éditions multiples répondant à des goûts et des projets différents

Le livre de bibliophilie, genre très vaste, est traditionnellement l’objet d’un texte célèbre et sa mise en page reste classique, comme par exemple Les Fables de La Fontaine, gravées par Gustave Doré. Il peut en effet être enrichi d’illustrations qui apportent une plus-value à l’objet livre. Il tient sa supériorité de la qualité du papier utilisé et de la rareté des exemplaires.

It’s clear, then, that the artist’s book holds a paradoxical place in the field of illustrated books: at one and the same time, it’s a bibliophile and more than that. A review of Jazz shortly after its publication sheds light on this point of view:

“Matisse has created an eminently decorative ensemble. We shouldn’t be surprised if this beautiful work is more of an easel painting than a book or engraving.

Jacques Guignard in the “Chronique du beau livre” in Le Portique magazine.

The artist’s book is an experiment: the painter uses the literary work as a support to shape a work that precedes public demand. The text is a source of inspiration for creation. The image becomes an autonomous component of the work. In addition, the typography is worked out and the layout original, the book object itself enters into the painter’s process of reflection and creation.

In the words of art historian Michel Melot, “literature is integrated into the art object, becoming an object in its own right, magnified in concrete terms by the impeccable typography […]”.

Variations in paper quality, rarity and layout can also be discerned in editions of the same illustrated work. Before the publication of a standard edition, made up of reproductions and financially more accessible, a first edition can be printed. This is characterized by a limited number of copies, justified by the artist, and often enhanced by one or more original prints on paper that is sometimes uncut.

For some works, there are also suites printed with large margins. This means that, along with the original stone, copper or wood, all the prints in the book are printed on larger paper, with margins. This was the case for Sable mouvant, written by Pierre Reverdy and illustrated by Pablo Picasso, printed in 1939: 80 suites on large-margin paper and 255 copies of the book.

They can then be sold independently and are suitable for framing. The text is no longer really important, and it’s essentially the painter’s productions that we’re interested in.

However, it remains difficult to describe a strict editorial scheme for illustrated books, as there are almost variations in the printing of each work, depending on various factors: the artist, the text, the publisher, the printer…

3) Le livre d’artiste : l’auteur et le peintre sur un pied d’égalité

Le livre illustré propose une réflexion intéressante sur la complémentarité des techniques artistiques. Cette synergie permet d’ouvrir de plus larges horizons créatifs qui mènent à une œuvre complète, intense et riche. L’art pictural se mêle à la littérature afin de créer un imaginaire plus vaste encore que celui proposé par l’auteur. Joan Miró refusait le terme d’illustrateur car il induit une prédominance du texte sur l’image, alors que c’est un travail qui a pour objectif d’aboutir à un équivalent plastique de la littérature.

4) The illustrated book, a collective effort

What makes illustrated books so special is that they are not only works of art, but also of craftsmanship. Many hands and souls are involved in the design of these works, which are the result of a collective effort. Art publishers are often at the origin of these projects, proposing a text to the artist and then accompanying him or her in the production of the models.

Ambroise Vollard, a famous publisher in the first half of the 20th century, worked with some of the greatest painters of his time, including Pablo Picasso, Pierre Bonnard, Georges Rouault and Marc Chagall. Ida Chagall, the painter’s daughter, recounts:

“Vollard talked about working on La Bible. He saw this book in several volumes. From 1931 to 1939, my father engraved 105 plates for La Bible. The work took place at Potin’s, and was immense because there were almost always 10 to 12 different states for each subject. During these years, Vollard came almost every day. He was passionate about the work and the search for papers. He continually encouraged the artist, and we no longer thought about the modest sums he paid for his work.”

The colossal amount of work carried out for the Bible also evokes the indispensable know-how of master engravers. These behind-the-scenes craftsmen help the artist with printmaking techniques that require real expertise in the choice of colors, papers and chemical processes.

5) Illustrated books: a paradoxical place on the art market.

Illustrated books are part of a reflection on the place of artworks in society and the art market.

Luxury editions were traditionally aimed at a financial and intellectual elite with an appetite for beautiful objects. Even in the twentieth century, buying such a book was still a socio-economic distinction and a matter for wealthy amateurs or simple enthusiasts.

In addition to this practice, many of these books, particularly those produced by artists close to the Surrealist movement, play with these codes. They use a variety of materials, some of which are not particularly noble, such as cardboard, and print editions that they produce by hand in very small runs (10 to 40 copies), without the need for a workshop. Most of these books were then distributed in a closed circuit, with artists sharing their works within their intellectual circles. They renewed the vocation of illustrated works: they were not intended for sale, and did not seek to seduce a certain public with sumptuous page layouts and high-end publishing. These books are created above all for the pleasure of creating, and to poke fun at the codes anchored in society. PAB has worked with artists such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Jean Hugo to create tiny books. He typographed and printed these original books at home, in very limited numbers.

The painter’s book also enables 20th-century contemporary art to find a foothold in everyday life. For those who are less familiar with modern works, because they break all established codes, the illustration of a popular text provides a point of connivance between the public and the painter. In the end, a book remains a classic object that belongs to our daily lives.

In these art pieces, the original illustrations by famous painters are hand-crafted, but remain subject to the text, as for example Au pied du Sinaï, by Georges Clémenceau, illustrated by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec in 1898.