Georges Braque

(1882-1963)

“Painter of contained richness, of silent truths, of deep, secret knowledge[1] “.

Georges Braque is one of the major artists of the twentieth century. “Together with Picasso, he invented cubism, one of the most important artistic revolutions of the period. Braque came from a family of house painters, and was himself destined to become a decorative painter. He grew up in Le Havre, where he befriended Raoul Dufy and Othon Friesz. He moved to a studio in Montmartre, Paris, in 1904. At the 1905 Salon d’Automne, the discovery of works by Matisse and Derain, brought back from Collioure where they had spent the summer, made a strong impression on him. Fauve painting, dynamic and full of enthusiasm, influenced his work over the following summer. Cézanne’s work quickly became a source of inspiration for him, all the more so as the painter from Aix-en-Provence, who died in October 1906, was in the news at the time: a retrospective exhibition paid tribute to him at the Salon d’Automne in 1907, as did the Bernheim-Jeune gallery.

The discovery of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, June-July 1907 (New York, Museum of Modern Art) in Picasso’s studio in late November/early December, marked the beginning of a dialogue between the two artists through their works – also nourished on the periphery by works by Matisse, such as Nu bleu souvenir de Biskra 1907 (Baltimore, Museum of Art) and Derain – that would lead them to Cubism. Braque spent several periods in L’Estaque, following in Cézanne’s footsteps. The 1908 Salon d’Automne rejected the landscapes he had painted there during the summer. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler presented them in his fledgling rue Vignon gallery from November 9 to 28. This was the first public exhibition of Cubism. Twenty-seven landscapes, with their pronounced volumes and lack of perspective, embody what Braque referred to as a tactile, palpable space, in which the objects, the subject, give the feeling of being in the same space as the viewer.

“Following in Cézanne’s footsteps, we’ve introduced a perspective that puts objects within reach of the hand and signifies them in relation to the artist himself. Bringing things closer to the viewer’s gaze, fostering the communion of the tactile and the visual. […] It’s good to make people see what you can, but if you can make them touch it at the same time, that’s even better.[2] “.

The dialogue between the two artists intensified. Braque spent the summer and early autumn of 1909 at La-Roche-Guyon, while Picasso was at Horta de Ebro. In the series of paintings devoted to the Château de La-Roche-Guyon, Braque gives as much pictorial importance to the space between objects as to the objects themselves. Picasso, for his part, produced portraits of Fernande in which surfaces are cut into facets. These works inaugurated Analytical Cubism. In Les Usines du Rio Tinto à L’Estaque, autumn 1910 (Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou), the subject is less and less legible. The two artists worked together during the summers of 1911 in Céret and 1912 in Sorgues. This was the beginning of the hermetic phase of Analytical Cubism, the moment when they were probably closest to each other, and when they competed in innovations to thwart the propensity of their representations to become too abstruse. “We had to get out of analytic cubism; we were aware of the danger that too much hermeticism, too much abstraction, could represent.[3] “. In Le Portugais (Basel, Kunstmuseum), Braque introduces trompe-l’œil surfaces into his painting for the first time: stenciled typographic elements, letters and numbers in block letters.

“In 1911, I introduced letters into my paintings. These were forms where there was nothing to deform because, being flat surfaces, the letters were out of space, and their presence in the painting, by contrast, made it possible to distinguish objects that were in space from those that were out of space.[4] “.

In Les Usines du Rio Tinto à L’Estaque, autumn 1910, the subject becomes less and less legible.

In the same year, he mixed various materials with paint (sawdust, sand, etc.) to enhance its tactile dimension and create relief. “I wanted to turn the brushstroke into a form of matter[5] “. His tactile sensitivity to matter is an omnipresent dimension of Braque’s work. In the spring of 1912, Picasso produced the first collage, Nature morte à la chaise cannée (Musée national Picasso-Paris), and a few months later, in the summer, Braque executed the first papier collé, Compotier et verre (The Leonard A. Lauder Cubist collection), referred to by Picasso as a “paperistic and pusiéreux [sic] process”.[6] “. With paper collage (synthetic cubism), which reintroduces real elements into pictorial space, representing only themselves, color returns to their painting. In 1914, paper collage evolved towards a more decorative and pictorial dimension, with the use of painted, speckled, gouached and overpainted paper. This is what is known as decorative cubism.

The war put an abrupt end to this extraordinary creative period. When war was declared in early August 1914, Braque was mobilized. It was the end of an era. “On August 2, 1914, I took Braque and Derain to the Avignon train station.[7] “. Braque was seriously wounded in the head in May 1915. His convalescence was long. Kahnweiler, a German national, is exiled to Switzerland, and his gallery’s assets, considered enemy property, are sequestered. At the end of November 1916 Braque signs a contract with Léonce Rosenberg’s gallery l’Effort moderne. In 1917 Braque was demobilized and discharged. He returned to painting with works in the tradition of synthetic cubism: figures and still lifes in dark tones. The war marked a break. His painting became charged with melancholy. From then on, his work developed in series. In September 1920, on his return from Switzerland, Kahnweiler reopened his gallery under his partner’s name, Galerie Simon, 29 rue d’Astorg. He resumed contact with his painters. Four escrow sales between June 13-14 1921 and May 7-8 1923 dispersed his gallery’s pre-war collection. They flooded the market with Cubist works at attractive prices.

Alongside still lifes, notably the guéridons, Braque undertook a series of chimneys (five between 1920 and 1927), and the Canéphores (1922), figures composed of a supple, undulating line, which led to a series of nudes until 1926-1927. The tactile dimension of the works from this period is due to the materiality of the paint, composed of a thick paste. Presented at the Salon d’Automne in 1922 among numerous still lifes, in a room entirely dedicated to Braque, the Canéphores provoked two opposing reactions: some saw in them a renunciation of Cubism in favor of the general trend towards a return to order. Matisse’s odalisques and Picasso’s classicizing language elicited similar assessments. For others, such as Carl Einstein, a great admirer of Braque, and Kahnweiler, they are, on the contrary, an extension of Cubism, a synthesis and a new departure.

Still Life with Sonata, 1921, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

In 1923 and 1924 Braque composed sets and costumes for various ballets. Les Fâcheux and Zéphy et Flor for Serge de Diaghilev’s ballets, and Salade for the Comte de Beaumont. Since Parade in 1917, a huge success and scandal, most avant-garde artists have collaborated with Serge de Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Rolf de Maré’s Swedish ballets and, to a lesser extent, the Comte de Beaumont’s Soirées de Paris. Between 1919 and 1924, Picasso, Léger, Derain and Matisse were also involved in decorative work for the stage.

Braque left Montmartre for Montparnasse in 1925. He moved to 6, villa Nansouty, which became rue du Douanier, now renamed rue Georges Braque. In 1927, he painted more austere still lifes against a black background. Tériade devoted the second issue of his “Confidences d’artistes” series, published in L’Intransigeant in 1928 and 1929, to Georges Braque, whom he saw as “one of the most intelligent, profound and poetically sensitive figures in contemporary painting. […] In painting, he does not want to

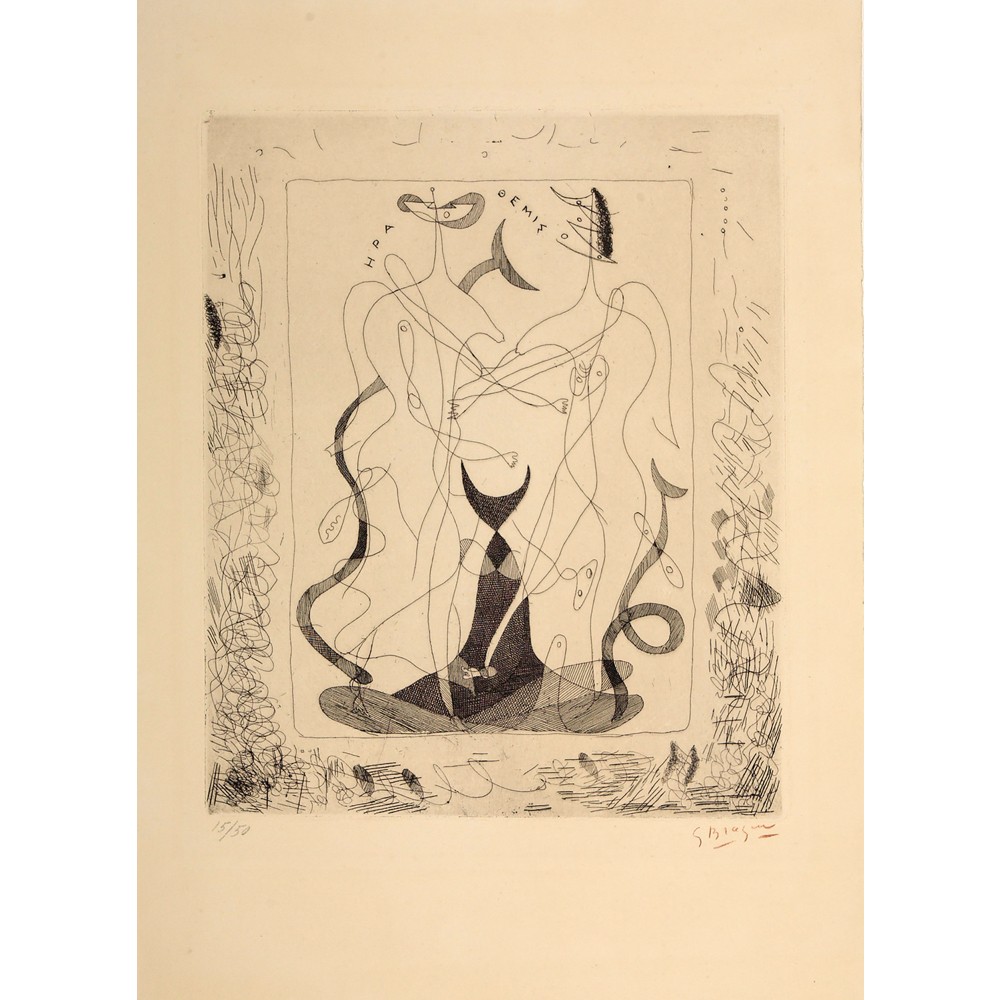

In 1931, he produced his first plaster engravings, inspired by figures of ancient Greek gods and heroes: Heracles, Niké. While Vollard continued to publish artists’ books in 1930 and 1931, he approached Braque in 1932. The artist chose to illustrate Hesiod’s Theogony, the great text of Greek mythology, and one of his favorite texts. Braque executed a series of sixteen etchings between 1932 and 1935. The figures are composed of a highly dynamic circulating line. Vollard’s accidental death in July 1939 interrupted the project – which was resumed and published by Maeght in 1955. Théogonie marks a turning point between the spirit of synthetic cubism and biomorphism. From then on, he used a supple, flowing arabesque line to create forms with organic accents, very much in vogue with artists of the period (Masson, Picasso).

In 1934, Carl Einstein publishes his monograph on Braque in French (Chroniques du Jour). The following year Braque met Jean Paulhan, then editor-in-chief of La Nouvelle Revue française. Paulhan began work on Braque le patron in May 1942, which was completed in August. In 1936, the artist began the cycle of interiors with women at easels or palettes, and black figures. Following in the footsteps of Matisse and Picasso, in 1937 he received the Carnegie Prize for La Nappe jaune, 1935 (private collection). Braque’s cubist works are shown at theEntartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition in Munich, which stigmatizes avant-garde art. In an increasingly oppressive political context, Braque executed a series of vanitas in 1938 and 1939, combining the themes of the studio and death. On September 3, 1939, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. The artist settles in Varengeville. He devotes himself to sculpting mythological subjects.

On November 7, 1939, the first retrospective of Braque’s work in America opened at the Arts Club of Chicago, designed in part by Paul Rosenberg.[9]. A few days later, on November 15, MoMA opened a Picasso retrospective(Picasso: Forty Years of His Art, until January 7, 1940).

The Theogony marks a turning point between the spirit of synthetic cubism and biomorphism.

Of Jewish origin, Paul Rosenberg closed his gallery in 1940. He took refuge in the Free Zone in Bordeaux. After the Armistice, Braque returns to Paris. The suicide on July 3 of his friend Carl Einstein, pursued by the Gestapo, affects him deeply. In 1941 he produced a new series of still lifes with black and red fish and Ateliers. The following year, he painted a series of interiors marked by the atmosphere of the war, still lifes with black teapots, and highly impastoed skulls. These works were exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in 1943, which devoted a retrospective to him (twenty-six paintings and nine sculptures). After D-Day, he returned to Varengeville. He undertook larger-scale works such as Le Salon de 1944 (Paris, Musée national d’Art moderne, Centre Pompidou), the largest of his interiors at the time. The Salon d’Automne after the Liberation presents a major Picasso retrospective. In the autumn, he begins the Billiards series, consisting of a total of seven paintings until 1949.

In August 1945, the artist underwent surgery for two stomach ulcers, and stopped painting for several months. In 1947, Aimé Maeght, who had inaugurated his Paris gallery on rue de Téhéran at the end of 1945 with a Matisse exhibition, became Braque’s main dealer. In June, he devotes a first exhibition to Braque, accompanied by a special issue of Derrière le miroir (n°4). Braque meets René Char through Yvonne de Christian Zervos. Char writes his first text on the artist, “Georges Braque intramuros”, then in Cahiers d’Art, on the occasion of the exhibition at Maeght’s, “Œuvre terrestre comme aucune autre et pourtant combien harcelée du frisson des alchimies”.[10] “. Maeght publishes Cahier de Georges Braque 1917-1947. The Venice Biennale awarded him the Grand Prix International de Peinture in 1948 for Le Billard, 1944 (Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou). He begins the Ateliers cycle. The Maeght gallery presents the first five in January 1949.

Along with Rouault, Léger, Chagall, Matisse and Germaine Richier, Braque takes part in decorating the interior of the Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce church on the Plateau d’Assy, a symbol of the post-war revival of sacred art led by Father Marie-Alain Couturier. He created a bronze bas-relief based on the Eucharistic symbol of the fish. The church was consecrated in 1950.

In 1951 and 1952, alongside large-scale works such as Atelier VI, VII and VIII, he painted small country landscapes. In June 1952, the issue of Derrière le miroir, which accompanied the Braque exhibition at Galerie Maeght, published the first text written by Alberto Giacometti on the artist: “Gris, brun, noir…[11] ”

Following on from Eugène Delacroix’s ceiling of the Galerie d’Apollon in 1851, and before Cy Twombly’s ceiling of the Salle des Bronzes Antiques in 2010, Georges Salles, then Director of the Musées de France, commissioned Braque in 1953 to decorate the ceiling of the Salle Henri II in the Musée du Louvre, which houses the Etruscan collections. The ceiling, entitled Les Oiseaux, was inaugurated on April 21, 1953. Braque completed the Ateliers series in 1956; at the same time, Picasso painted his “Interior Landscapes”, set in California as a tribute to Matisse, who had died in November 1954.

Braque won the Grand Prix International de Peinture at the 1948 Venice Biennale with Le Billard.

After the Ateliers (I to IX), the last years are dominated by seaside and countryside landscapes, skies with birds. The theme of the bird, in majesty at the Louvre, which according to Braque “sums up [his] entire art”, occupies a central place in his later work. It is present, among other motifs, in seven of the nine Ateliers (except I and III), and from 1956 onwards it is the central subject of a series of paintings. L’Oiseau et son nid (Paris, Musée national d’Art moderne, Centre Pompidou) and A tire d’aile, premier état – completed in 1961 (Paris, Musée national d’Art moderne, Centre Pompidou) are his first major paintings on this theme, followed by Oiseaux noirs, 1956-1957 (Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Fondation Maeght) and the famous L’Oiseau noir et l’oiseau blanc, 1960 (private collection). His last landscapes (1955-1963), large, horizontal and long, are made up of thick material and evocative bands of sky and earth, at a time when abstraction was dominating the art scene. They are sometimes punctuated by a boat, a plough or a weeder, the artist’s last work.

In 1961, a major exhibition organized by Jean Cassou, L’Atelier de Georges Braque, was presented at the Musée du Louvre. It was the first time such a tribute to a living painter had been held in the institution. Georges Braque dies on August 31, 1963. Giacometti makes six drawings of Braque on his deathbed, three of which are published in the issue of Derrière le miroir dedicated to the painter from Varengeville, with a text by the Swiss artist that dwells on the deceased’s last landscapes.

“Georges Braque has just died. […] Of all this work, I look with the greatest interest, curiosity and emotion at the small landscapes, still lifes and modest bouquets of the last, the very last years. I look at this almost timid, imponderable painting, this nude painting, of a completely different boldness, of a much greater boldness than that of the distant years; painting that is for me at the very cutting edge of today’s art with all its conflicts[12] “.

On September 3, 1963, a state funeral was held in his honor in the Cour Carrée of the Musée du Louvre. André Malraux delivered a eulogy, “a tribute to the memory of Georges Braque, […] one of the greatest painters of the century.[13] “.

Georges Braque engraver

Georges Braque produced around 70 black and colored etchings between 1907 and 1962, and almost 150 black and colored lithographs between 1921 and 1963, including just over eighty illustrations. The catalog raisonné of Braque’s engraved works was designed by Dora Vallier 1982.

Although he began etching proper before lithography, these two practices were concomitant until the end of his career. Braque went from one to the other.

His first contact with etching dates from 1907. He executed an etching of a Cubist nude. There are eleven Cubist etchings, eaux-fortes and drypoints (1907-1912), most of which only gave rise to rare trial proofs. Job and Fox, printed by Delatre, were published in editions of 100 by the young art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who bought Braque’s first paintings in the summer of 1907. In the 1950s, Aimé Maeght produced several editions printed by Georges Visat (1950, 1953 and 1954). Kahnweiler and Maeght are the two publishers of the artist’s prints.

Braque returned to etching in 1930 with three essays and a project to illustrate Hesiod’s Theogony proposed by Ambroise Vollard. Greek civilization was a source of inspiration for Braque’s later work. From 1950 onwards, other themes appeared in his etchings, such as birds, heads and flowers.

He produced his first lithograph, a still life, for Kahnweiler in 1921. In contrast to his etchings, Braque’s lithographs were largely still lifes. His meeting with Fernand Mourlot in 1945 marked the start of an exceptional production that began with the Teapot series, followed by numerous fruit still lifes. At the same time, he began to paint Greek-inspired subjects, followed by birds, a major theme in Braque’s work. At Mourlot, he works with Henri Deschamps.

Braque contributed illustrative prints to numerous works. These collaborations reveal his artistic affinities and friendships for almost forty years. Erik Satie, Carl Einstein Francis Ponge, René Char, Jean Paulhan, Pierre Reverdy.

[1] Tériade, “L’Épanouissement de l’œuvre de Braque”, Cahiers d’Art, Paris, 1928, no. 10, reprinted in Tériade, Écrits sur l’art, Paris, Adam Biro, 1996, p. 137.

[2] André Verdet, Entretiens, notes et écrits sur la peinture, Paris, éditions Galilée, 1978, p. 25-26.

[3] Ibid, p. 21.

[4] Dora Vallier, “Braque, la peinture et nous”, Cahiers d’Art, Paris, 1954, p. 16.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Letter from Picasso to Braque, October 9, 1912, quoted in Picasso et Braque. The Invention of Cubism, William Rubin (ed.), cat. exhibition, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1992, p. 385.

[7] D.-H. Kahnweiler, My galleries and my painters. Interviews with Francis Crémieux Paris, Gallimard, 1982, p. 68.

[8] Tériade, “Georges Braque”, L’Intransigeant, April 3, 1928, reprinted in Tériade 1996, op. cit. , p. 137.

[9] The exhibition was then shown in Washington (Philipps Memorial Art Gallery – now the Phillips collection) and then in San Francisco (San Francisco Museum of Art) until March 1940.

[10] René Char, “Préface à l’exposition Georges Braque”, Cahiers d’Art, Paris, 1947, p. 334.

[11] Derrière le miroir, Georges Braque, Paris, Maeght éditeur, June 1952, no. 48-49.

[12] Alberto Giacometti, “Georges Braque”, Derrière Le Miroir, Paris, May 1964, no. 144-145-146.

[13] André Malraux, “Hommage à la mémoire de Georges Braque”, September 3, 1963. Œuvres complètes, Écrits sur l’art, Paris, Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 2004, tome IV, p. 244.