Fernand Léger

(1881-1951)

Fernand Léger is one of the great figures of modern art in the first half of the 20th century. His work is highly personal, immediately identifiable and firmly rooted in his era.

His family intended him to become an architect. In 1900, he left his native Normandy for Paris. As a free student, he attended the classes of painter Jean-Léon Gérôme at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, then those of his successor Gabriel Ferrier. He also attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. His early works are marked by Impressionism.

The discovery of Cézanne's work, particularly at the retrospective held at the Salon d'Automne in 1907, was a revelation, as it was for many other artists of his generation, including Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. "Cézanne, the master of us moderns [1]." Léger followed in the footsteps of the Aix master, decomposing reality into geometric forms set in perspective. "Treating nature through the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, all set in perspective [2]."

At the same time, he moved to La Ruche, where he rubbed shoulders with Blaise Cendrars, Robert Delaunay, Marc Chagall and Alexandre Archipenko. He exhibited at the Salon d'Automne in 1908 and 1909. In Jacques Villon's studio in Puteaux, Léger takes part with Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger and Raymond Duchamp-Villon in the meetings that give rise to the Puteaux group and the Section d'or.

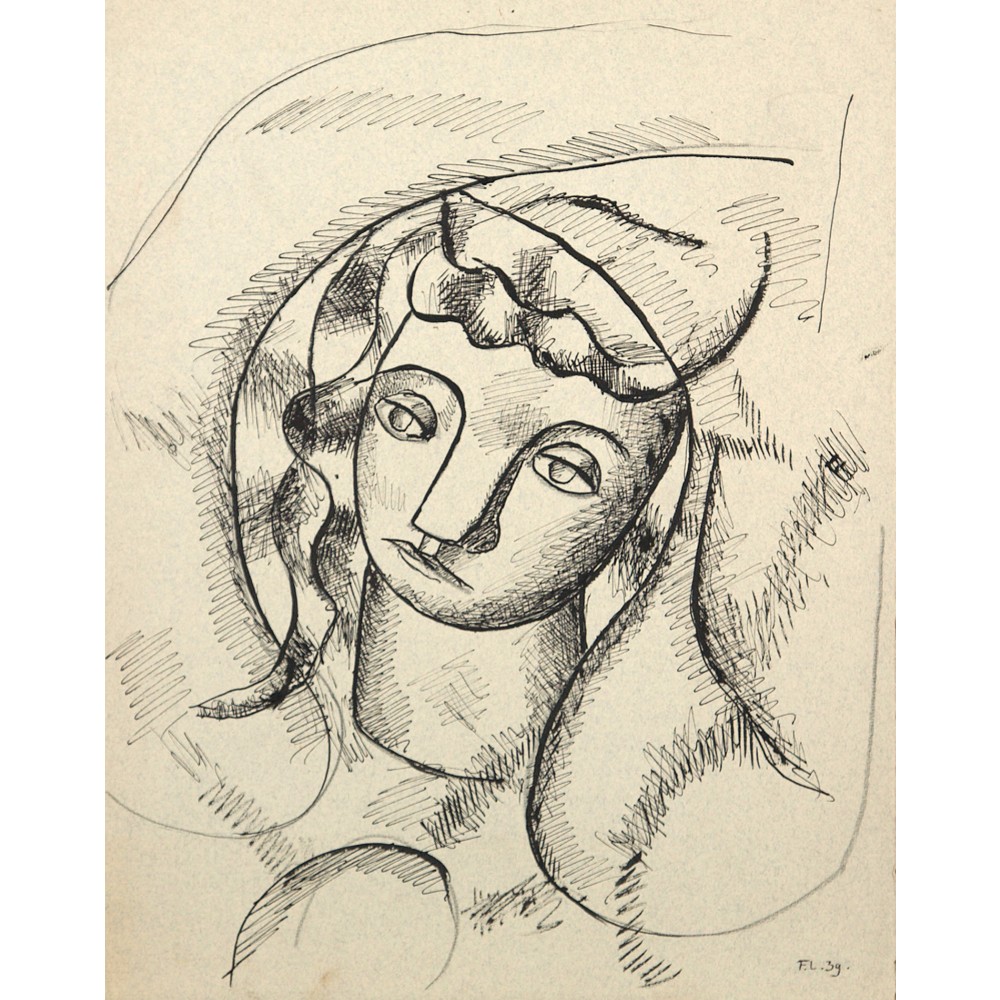

Étude pour composition aux deux parroquets, 1939, Indian ink and pencil on paper © ADAGP, Paris, 2024.

His work is part of the classical tradition that gives primacy to drawing. He insists on the highly thought-out, constructed dimension of his work, which is very sensitive indeed. "I don't know how to improvise[3]"he says. His works combine this classical background with signs of modernity. Léger's aim was to create art in tune with the times, art in tune with what was new and modern. "A work of art must be significant in its own time, like any other intellectual manifestation.[4]". In this context, let's recall Marcel Duchamp's famous remark while visiting the Salon de la locomotion aérienne in the company of Constantin Brancusi and Léger: "Painting is finished. Who could do better than a propeller? Say, can you do that?[5] However, Léger remained a painter, and although his work resonated with the times, unlike that of the Futurists, he was not an apologist for modernity. In 1912, in Les Peintres cubistes, méditations esthétiques, Guillaume Apollinaire counted Léger among the painters of orphism, a derivative of cubism that gave pride of place to the light created by color. The same year, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, famous dealer for Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris, offers Léger his first solo exhibition, followed the next year by an exclusive contract.

In the "Contrastes de formes" series of 1913, Léger's new language is the equivalent of the fragmentation of vision and syncopated rhythm he observes everywhere. Beyond this group of works, the "principle of contrasts" and their intensity permeate all of Léger's work.

Fernand Léger was one of those artists who took up the pen, like Henri Matisse and Wassily Kandinsky among his contemporaries. For two successive years, in 1913 and 1914, he gave a lecture at the Vassilieff Academy: "Les Origines de la peinture contemporaine et sa valeur représentative" on May 5, 1913 (published in two parts in Monjoie ! n°8, May 29, 1913 and n°9-10, June 14-29, 1913) and "Les Réalisations picturales actuelles" on May 9, 1914 (published in Les Soirée de Paris n°25, June 15, 1914). These two texts inaugurated a whole series of writings until his death in 1955.[6]. Like many artists, his departure for the front in August 1914 marked a break with the past. It put an abrupt end to a period of exceptional creative effervescence. Georges Braque, André Derain and Guillaume Apollinaire also left. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a German national, moves to Switzerland, where he stays for the duration of the conflict. His gallery and stock were sequestered. Léger is mobilized in 1914 in the Engineers. He drew a great deal, always breaking down shapes into simple geometric volumes (soldiers, cannon breeches, etc.). After suffering a gas attack, he was hospitalized and discharged in 1917. During his convalescence, he undertook the large-scale composition with its Cézanne-like subject, La Partie de cartes, dated December 1917 (Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum), born of the observation of his fellow students. The forms are broken down into geometric volumes.

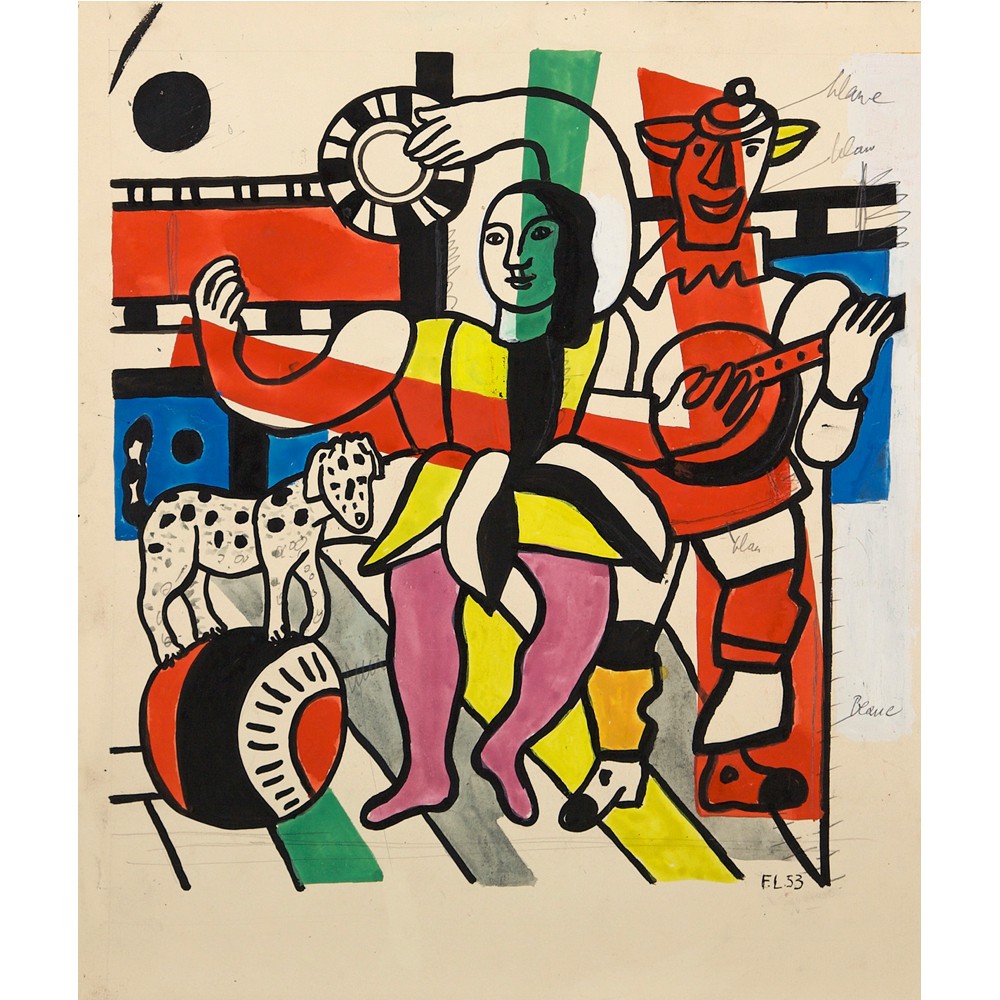

Model for Cirque,1950, pencil, gouache, Indian ink on paper © ADAGP, Paris, 2024.

The war had a profound effect on him. Léger became aware of the domination of civilization by the machine. For several years, his work revolved around mechanical iconography. In 1918 and 1919, his work was dominated by the themes of disks and the city. He plays with contrasting forms and colors, which oppose and respond to each other. He creates fragmented, discontinuous spaces that suggest the hustle and bustle of modern life. The discs recall, in a different language, those of Robert Delaunay in 1912-1913, and beyond, his research into circular forms. The Delaunays sought to create an art form that would embody modern life, reflecting the simultaneity of the world. The Discs foreshadow La Ville of 1919 (Philadelphia Museum of Art). With its brightly colored planes, escaped letters from posters or billboards, and balustrades, it translates urban modernity. Léger created a number of different versions: Les Hommes dans la ville (Men in the City), L'Échafaudage (Scaffolding), Le Passage à niveau (Level Crossing) and others. Through the themes of the city and the machine, the artist develops a "new realism". The human figure also occupies a privileged place. It is desensualized, treated as an equal to objects, subjected to a machinist aesthetic, reflecting the anonymity and harshness of modern life/civilization. It's the object-figure: "For me, the human figure, the human body, is no more important than keys or bicycles [...]. One must consider the human figure not as a sentimental value, but solely as a plastic value.[7]. " La Lecture, 1924 (Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne), is a major work from this period.

In 1919, Léger signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg's L'Effort moderne gallery, which presented his first solo show in February.

Restrained during the years of conflict, artistic activity experienced extraordinary dynamism in the 1920s, aptly named the "Roaring Twenties". It was a very flourishing period. Aesthetically, these years were a counterweight to the extremely innovative and experimental period that preceded the war. Many artists returned to a more traditional, classicist aesthetic, which helped to renew their language. Think of Pablo Picasso's "ingresque" period, with its massive figures, or Henri Matisse's odalisques. Léger's round figures, with their simplicity of form, have something archaic about them. In the 1920s, his still lifes bore similarities to the purist aesthetic (beyond cubism) advocated by Amédée Ozenfant and Le Corbusier. Léger's Hélices, executed in 1919, appeared in 1921 in issue no. 4 of their multidisciplinary magazine L'Esprit Nouveau. Like Léger, Le Corbusier envisaged his creation, architecture, in harmony with the times.

During the 1920s, artists diversified their practice. They became increasingly interested in fields other than painting, such as book illustration, decorative painting, ballet sets and costumes, tapestry, stained glass and ceramics.

Léger produced his first illustrated book, J'ai tué. Prose de son ami Blaise Cendrars in 1918 (Paris, La Belle édition). He shared with Cendrars a certain fascination for the elements of modern life. The following year, he illustrated La Fin du monde filmée par l'Ange Notre-Dame (Paris, Éditions de la sirène, 1919) by the same author. He repeated the experience with André Malraux's Lunes en papier (Paris, Galerie Simon, 1921).

It was also the golden age of Serge de Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and Rolf de Maré's Swedish Ballets. Artists actively collaborated in designing sets and costumes. Diaghilev enlisted Picasso for eight ballets between 1917(Parade) and 1924(Le Train bleu), André Derain(Boutique fantasque created in 1919), Henri Matisse(Le Chant du Rossignol also in 1919). Léger collaborated with Les Ballets suédois in 1922. He designed the sets and costumes for Skating Rink, a ballet based on a poem-argument by Riciotto Canudo, music by Arthur Honegger and choreography by Jean Börlin. The following year, at a time when African imagery was permeating all areas of creation, he designed the sets and costumes for La Création du monde, a ballet based on an argument by Blaise Cendrars, music by Darius Milhaud and choreography by Jean Börlin, premiered on October 25, 1923 at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. He was a regular performer until 1950.

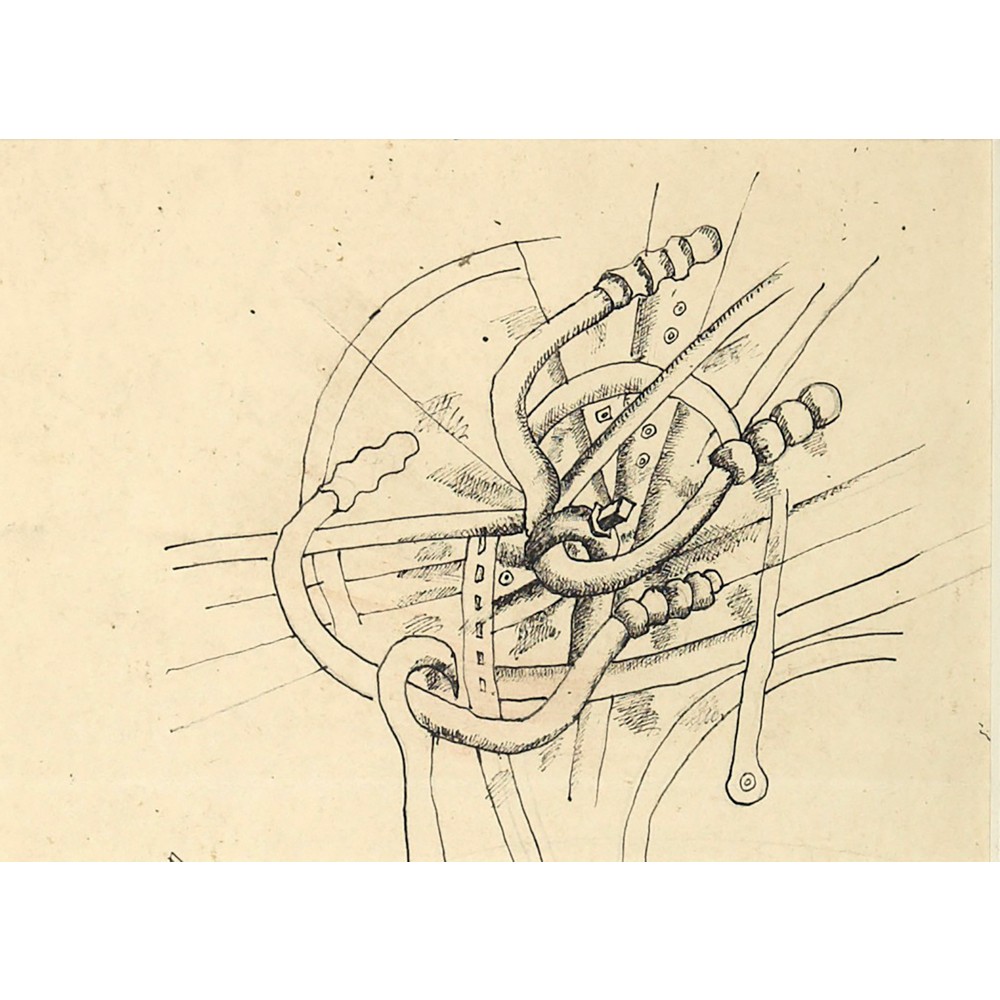

La Parade,1953, pencil, gouache, Indian ink on paper © ADAGP, Paris, 2024.

A moving image with immense technical and artistic possibilities, cinema fascinated a number of artists at the time, who ventured into this discipline. Viking Eggeling, La Symphonie diagonale, which Léger saw in 1924, Hans Richter, Rythmus 21 (1921), Man Ray, Le Retour à la raison (1923), René Clair and Picabia, Entr'acte (1924), Marcel Duchamp, Anemic cinéma (1926). Léger was particularly interested in this young medium. He admired Sergei Eisenstein, Erich Von Stroheim and Chaplin. He produced several poster designs in 1922 for Abel Gance's La Roue, in which Blaise Cendrars took part as assistant director.

"Cinema made my head spin. [...] It all started when I saw the close-ups of Abel Gance's La Roue. It was the close-up that made my head spin. So I was determined to make a film.[8]. "

In 1924, he created the sets for Le Laboratoire in Marcel L'Herbier's film L'Inhumaine, in which Pierre Chareau and Robert Mallet-Stevens also collaborated. That same year, Léger directed Le Ballet mécanique with Dudley Murphy, an experimental film in which he affirmed the object's plastic sufficiency. Le Ballet mécanique, the "first film without a scenario", was first shown in Vienna in 1924, then in Paris in November. Following the film, objects took on a pre-eminent role in his painting. Most often isolated and depicted in close-up, they make up large still lifes painted between 1924 and 1927. In some of his paintings, Léger takes up the compartmentalized structure of rectangular modules of unequal size, slicing up space like successive planes. In Les Quatre chapeaux (Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne), the same object is depicted in several aligned copies, reminiscent of the moving image. The use of close-ups is also found in his depictions of figures.

In 1924, with Amédée Ozenfant, Marie Laurencin and Alexandra Exter, Léger founded the Académie de l'art moderne, located at 86 rue Notre-Dame-Des-Champs in Paris. Ozenfant taught there until 1928. In 1934, it became theAcadémie de l'art contemporain. Ozenfant further diversified his activity, producing cartons for carpets at the request of Marie Cuttoli, creator of Myrbor. His language of geometric shapes and flat colors was perfectly suited to transcription into wool. Around 1927, Robert Mallet-Stevens purchased a long rug by Léger (357 x 130 cm) for the grand salon of his private mansion (Paris, MAD).

At the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris in 1925, Léger painted murals for the winter garden hall of the French Embassy pavilion designed by Robert Mallet-Stevens (a pavilion created by the Société des Artistes Décorateurs under the patronage of the Ministry of Fine Arts). He is also represented in Le Corbusier's Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau, alongside works by Amédée Ozenfant, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Jacques Lipchitz and Juan Gris: Fernand Léger, Le Balustre, 1925 (New York, MoMA).

Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau, Photo: Marius Gavot © ADAGP, Paris, 2024.

In 1928-1929, the focus shifted to objects in space, heralded by Composition à la feuille, 1928 (Zurich, Kunstmuseum). Static objects now seem to float in space. Léger retained the principle of the close-up. Mechanical workings give way to organic elements at a time when a biomorphic tendency characterizes creation. New types of objects, from the plant, animal and mineral worlds, enter the scene. He draws and paints discarded objects and natural elements: branches, roots, leaves, flints, stones. His language became more flexible, even when it came to the figure. The theme of dancers was omnipresent in 1929 and 1930. Léger's work was very topical at the time. In 1928, Alfred Flechtheim's gallery presented his first solo show in Germany, a "dazzling exhibition"(Cahiers d'Art, 1928, p. 93). The same year, the first monograph on Léger was published by Cahiers d'Art, edited by Tériade. In November 1930, Paul Rosenberg's gallery devoted an exhibition to Léger.

Invited by Sara and Gérald Murphy, Léger visited New York for the first time in 1931, "the most colossal spectacle in the world", he wrote. "New York has a natural beauty, like the elements of nature, like trees, mountains, flowers. This is its strength and variety[9]. " The Kunsthaus Zurich presented a retrospective of his work in 1933, and the same year Christian Zervos devoted an issue of Cahiers d'Art to the artist's work. In April 1934, Marie Cuttoli showed Léger's "Objets" in her rue Vignon gallery.

No doubt in reaction to the immensity of American space, in the mid-1930s Léger's compositions tended towards increasingly imposing dimensions, such as Composition aux deux parroquets, 1935-1939, measuring 4 x 4.80 meters (Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne). During this period, well-finished compositions (reminiscent of advertising aesthetics) alternated with compositions of objects in space, with less strong contrasts between motifs. Léger made a second trip to New York in 1935 for the retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago.

In 1936, for the Exposition internationale des Arts et Techniques appliqués à la Vie moderne, the French government commissioned several decorations: for the Solidarité nationale pavilion built by Robert Mallet-Stevens, for the Union des Artistes modernes (UAM) pavilion and for the Palais de la Découverte. The artist creates six panels, including Le Transport des Forces (Paris, FNAC, on deposit at the Musée National Fernand Léger, Biot). The same year, he returned to set design for Serge Lifar's ballet David triomphant, with music by Rieti, which premiered at the Maison internationale des étudiants universitaires theater in Paris on December 15, and was revived at the Paris Opéra in May 1937. He also creates the sets and costumes for Naissance d'une cité, based on an argument by Jean-Richard Bloch. Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud and Jean Wiener composed the music. It's an opera, a total spectacle combining theater, circus, music hall and ballet.

He returned to the United States in September 1938 to give a series of lectures at several American universities, including eight at Yales with Alvar Aalto and Amédée Ozenfant on "Color in Architecture". During this stay, Léger met Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller, who commissioned him to decorate one of the fireplaces in the grand salon of the apartment at 810 Fifth Avenue in New York, designed by architect Wallace K Harrison and decorated by Jean-Michel Frank. A decoration of similar shape and size, Le Chant de Matisse (1938), frames the other fireplace in the living room directly opposite (Houston, Museum of Fine Arts). The walls of the room are adorned with works by both artists and their peers, including a large still life by Picasso from 1931, Pichet et coupe de fruits (private collection). On his return to France, he painted two monumental compositions: Adam et Eve and Composition aux deux parroquets (Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne).

In October 1940, from Marseille, Léger leaves occupied France for the United States. He was invited to teach at Mills College in California. He went there in the summer of 1941. The following year, MoMA bought Le Grand Déjeuner from Paul Rosenberg. Along with many compatriots, the artist takes part in the Artists in Exile exhibition organized by Pierre Matisse in his New York gallery. He creates a mural, Les Plongeurs, for the dining room of architect Wallace K. Harrison's house in Huntington, Long Island. Harrison in Huntington, Long Island. The dissociation of color and drawing that pervades his painting during his stay across the Atlantic is inspired by the lights of Broadway.

"In 1942 when I was in New York, I was struck by the Broadway spotlights sweeping down the street. You're standing there, talking to someone, and all of a sudden he turns blue. Then the color fades, another comes along and he turns red, yellow. This color, the color of the spotlight, is free: it's in space. I wanted to do the same thing in my paintings. [10]."

This principle characterizes the last period of Léger's work. Black rings counterbalance color. The artist travels to Canada in 1943. He discovered the town of Rouses Point near Lake Champlain, where he spent the summer. Enchanted, he returned regularly thereafter. He began the American Landscapes series. At an exhibition of his work in Montreal, he meets Père Marie-Alain Couturier, a key figure in the post-war revival of religious art.

Léger exhibits regularly (Chicago, Boston, New York, Quebec, Montreal) and gives lectures on several occasions in the United States and Canada. In March 1945, he takes part in the European Artists in America exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

The American world inspired him to create compositions using the discarded objects of industrial society among plant elements, as in Adieu New York, 1946 (Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne), completed on his return to France.

He returned to France in 1946. His work from the war years was exhibited at the Galerie Louis Carré on avenue de Messine. In 1947, he took part in the inauguration of the Maison de la Pensée française (House of French Thought) in aid of the Union nationale des intellectuels (National Union of Intellectuals). Léger takes over the direction of the Académie de Montmartre, created by Fernand Cormon, 104 boulevard de Clichy. His fluency in English attracts many demobilized GIs, including Kenneth Noland, Sam Francis and Ellsworth Kelly.

After the war, the protagonists of modern art were glorified as historical figures. Almost all of them were involved, or very involved, in public or private decorative projects. Since the 1930s, Léger has been strongly committed to architectural painting, the interaction of color with architecture. The scope of his work changed in the years following the war. On the initiative of Père Couturier, he participated with other artists in the decoration of the church of Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, designed by architect Maurice Novarina on the Plateau d'Assy, a manifesto in terms of sacred art and modernity. Léger designed a large mosaic for the building's façade.

A member of the Communist Party since the post-war years, he went to Wroclaw, Poland, at the end of August 1948, for the World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace. Picasso also attended with Paul Éluard. In Les Loisirs - Hommage à Louis David, 1948-1949 (Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne), Léger intends to return to a direct art form, understandable to all. He painted popular leisure activities and, with them, the paid vacations obtained in 1936 under the Front Populaire. The figures are the actors of history in the present.

In 1949, Père Couturier called on him again for the Sacré-Coeur church in Audincourt. Léger designed seventeen stained-glass windows on the theme of the instruments of the Passion to frame the nave and choir. At the same time, Henri Matisse works on decorating the Rosary chapel of the Dominican Sisters in Vence. He went on to create other stained-glass windows, notably for the University of Caracas in 1953.

From 1950 onwards, Léger explored polychrome ceramics in Biot at the studio of Roland Brice, one of his former students. He immediately associated this new practice with his preoccupation with mural art that could go beyond the limits of the painting. His first works were bas-reliefs. Ceramic sculptures, such as the large polychrome flowers, saw the light of day in 1952.

A major publisher of artists' books alongside the magazine Verve, Tériade published Le Cirque with illustrations and text by Léger in 1950, followed by La Ville after the artist's death in 1959. In March 1951, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, the Louis Carré Gallery in New York paid tribute to Léger with the 70th Anniversary Exhibition. Exhibitions followed, as did commissions. Architect W. K. Harrison commissioned Léger to decorate the Great Hall of the Palais des Nations Unies in New York. In 1954, Léger commissions stained glass and mosaics for the University of Caracas. He creates a mural for the dining room of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler's house in Saint-Hilaire.

Léger bought a property in Biot in 1955, called Mas Saint-André, to be closer to Roland Brice's studio. The artist died shortly afterwards on August 17. The Musée National Fernand Léger in Biot, built on the grounds of his property by architect André Svetchine, was inaugurated in 1960.

[1] Interview with André Verdet, in André Verdet, Entretiens notes et écrits sur la peinture, Nantes, Éditions du Petit véhicule, 2001 [1978], p. 58

[2] Letter from Paul Cézanne to Émile Bernard, Aix-en-Provence, April 15, 1904, quoted in Émile Bernard, Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne et lettres, Paris, [1920], p. 72.

[3] Remarks by Fernand Léger reported by Dora Vallier: "La vie fait l'œuvre de Fernand Léger. Propos de l'artiste recueillis par Dora Vallier", Paris, Cahiers d'Art, 1954, p. 157.

[4] Fernand Léger, "Les Réalisations picturales actuelles" published in Les Soirée de Paris, n°25, June 15, 1914, reprinted in Fonctions de la peinture, Paris, Gallimard, 1997, p. 39.

[5] Remarks by Fernand Léger reported by Dora Vallier in Vallier 1954, op. cit., p. 140.

[6] Fernand Léger's writings are collected in Fernand Léger, Fonctions de la peinture, Paris, Denoël-Gontier, 1965, Gallimard, 1997.

[7] Fernand Léger, "Comment je conçois la figure", Fonctions de la peinture, Gallimard, 1997, p. 76. See also Vallier 1954, op. cit. p.153.

[8] Remarks by Fernand Léger reported by Dora Vallier in Vallier 1954, op. cit., p. 160.

[9] Fernand Léger, "New York", Paris, Cahiers d'Art, n°9-10, 1931, pp. 437-439.

[10] Remarks by Fernand Léger reported by Dora Vallier in Vallier 1954, op. cit., p. 154.