Michel Guino

(1926-2013)

Michel Guino was born in Paris on September 28, 1926, to Gabrielle Borzeix and Richard Guino, the third of six children. It was in the studio of his father, a sculptor of Catalan origin, that he came into contact with the world of art and form from an early age. After attending the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in 1943, the following year he entered the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he met César, Albert Féraud and Philippe Hiquily, who had also studied with Marcel Gimond. In 1946, Michel Guino moved with a group of artists to Oppède-le-Vieux, a village in the Vaucluse region. There, in the absence of marble or bronze, too expensive for his fledgling career, Guino worked mainly with stone, which he found in abundance, and plaster, which was inexpensive. Driven by the same concern for economy, he began to explore salvaged materials. In 1948, he married Lise Prévost, from whom he later separated, but with whom he had three children: Clotilde, Isabelle and Guillaume. That same year, he discovered the work of Julio Gonzalez, a Catalan like his father, whose work enlightened and stimulated him, showing him the way to metal.

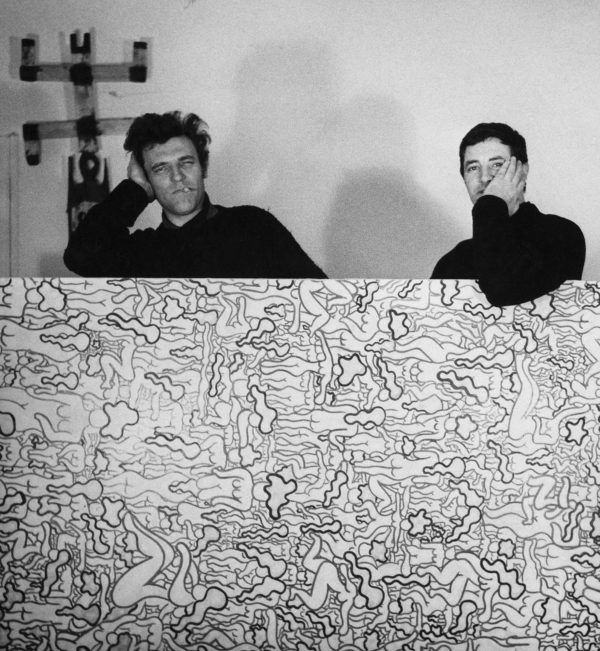

With Hiquily in 1962

In 1951, he fully embraced metal sculpture: brass, lead and iron became his materials. Metal," writes Guino, "allows us a new space, a more cosmic conception of form and light, which remains the real material to handle. His first metal sculptures were mainly spindly figures made from salvaged metal objects: horse-shoeing nails, keys and foundry dross were his raw materials. He then progressively explored and experimented with abstraction: "Initially largely figurative, his works soon became lighter, purer and more ethereal, while remaining marked for a long time by obvious references to human morphology", writes Jean-Luc Epivent.

By the end of 1956, the figure had given way to abstract compositions. He assembles fragments of bells to create sculptures that are at times aerial, evoking sails inflated by the wind; other hieratic structures seem to stretch skywards; remains of shells in copper or brass offer him the material for creations teeming with new forms.

From the mid-fifties, he exhibited regularly in galleries, biennales and salons: the Creuze, Iris Clert and Claude Bernard galleries were among the first prestigious Parisian galleries to invite him to exhibit. He also exhibited with Rasmussen at Galerie AAA and Marcel Zerbib at Galerie Diderot.

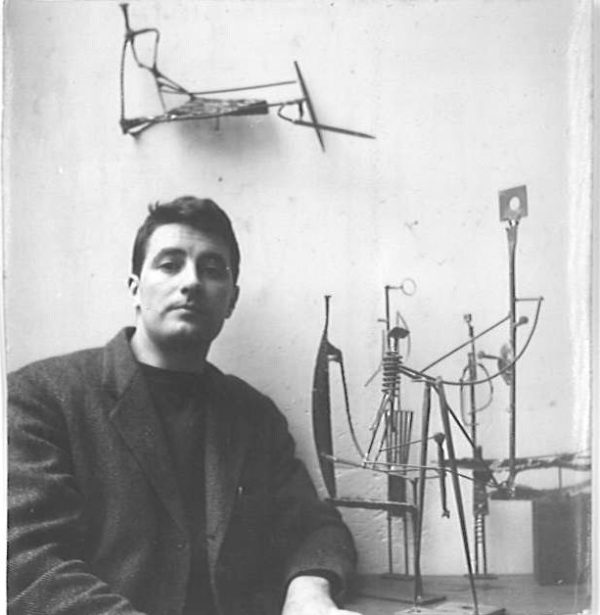

Around 1954 with his character sculptures

In 1959, Michel Guino exhibited at the first Paris Biennial and won the Prix de la Critique for Les pétales de l'espaces, followed by the Grand Prix de la Sculpture de la Ville de Marseille, which acquired Le manteau vide for the Musée Cantini. In 1961, thanks to the support of Alberto Giacometti, he was also awarded the Prix André Susse "for his body of work".

As early as 1960, he found jet engine blades and propellers in scrapyards, which became one of the main materials of his art, almost a signature. He let his taste for industrial forms shine through, and through a skilful transmutation, by introducing chaos, he brought poetry to life.

When he's not using mechanical elements, he cuts shapes from iron and stainless steel and hammers them together before welding the irregular plates into aerial architectures. "With Guino, play and chance are subject to his intuitive knowledge of the material, tamed by infallible craftsmanship", writes Lydia Harambourg.

Throughout his life, Michel Guino met many artists and personalities with whom he had enriching exchanges, such as Marcel Duchamp and Georges Bataille, whom he met in 1960 at the home of Marie-Laure de Noaille, or Jean-Luc Godard, who bought his robot-work Prométhée in 1965.

Guino looking for raw materials at a scrapyard, circa 1960

In 1964, thanks to the encouragement of his friend and architect Elie Azagury, the artist also began to question the necessary relationship between architecture and sculpture: "I've always wanted to place sculpture in a modern ensemble," says Guino, "not as a simple furnishing object, but as a sign charged with human presence. He thus created his first monumental work in Agadir, during the construction by Azagury of a children's center. This marked the beginning of a series of monumental works that he would continue to produce until the end of his life. In 1970, for example, he and his friend Albert Féraud created a large metal fresco for the Faculté des Arts, Lettres et Sciences Humaines in Nice, and his Don Quichotte, evoking ocean liners, near the Musée des Sables in Port Barcarès.

In 1965, he worked with the Russian poet, artist and publisher Ilia Zdanevitch, known as Iliazd, whom he had met ten years earlier, on the illustration of Paul Eluard's poem Un Soupçon.

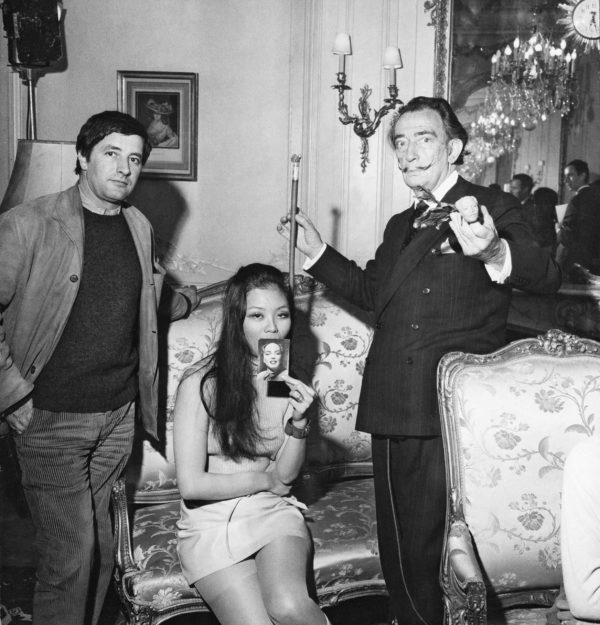

In 1966 Michel Guino met Dali, who commissioned a small sculpture of Mao's head mixed with that of Maryline Monroe, which he produced in 1967.

With Dali on May 3, 1967, at the Hotel Meurice.

After working extensively in abstraction, he returned to figurative art in 1970, creating the " Machin Chose " and " L'Homme qui marche " series of robots that look ready to move.

During this period, he also invented game sculptures, tables, chess sets and jewelry, assembling electronic circuits as well as sliced piano pedals and various salvaged objects. In the words of art critic Lydia Harambourg, he creates a "baroque and futuristic universe, often tinged with disquiet". Indeed, for Michel Guino, engraver, draughtsman and multi-talented creator, sculpture represents "the most restless of arts".

1970 was also the year he met Corinne Charpentier, whom he married a few years later and from whom he had a daughter, Ariane, who was born in 1973, two days before the death of her father Richard. Mixed emotions seem to have often accompanied Michel Guino's life, and everyone recognizes his charm, despite his strong character.

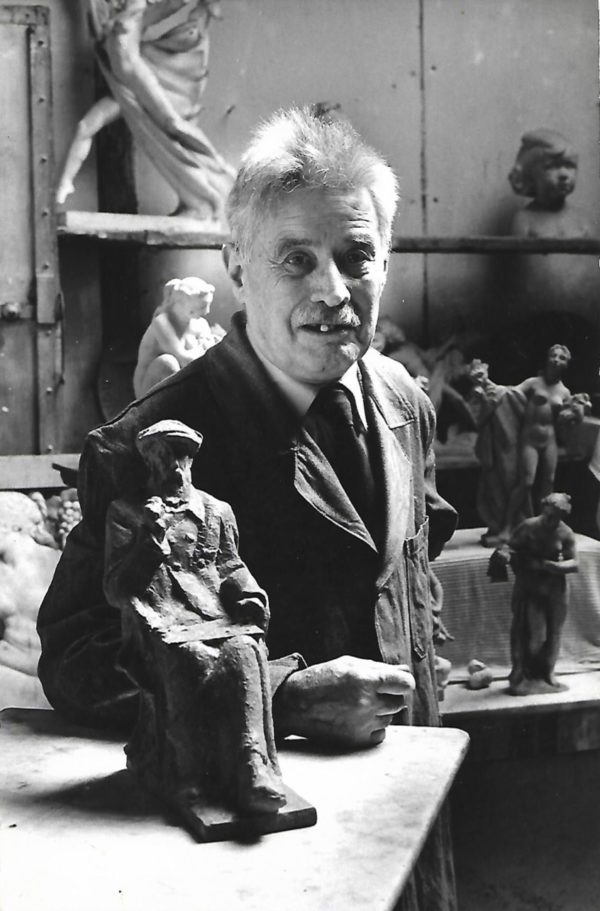

Richard Guino in his studio in Antony, 1967

For several years, Michel Guino took a back seat, as it were, to work on the recognition of the role played by his father in the creation of Auguste Renoir's sculptures. Indeed, from 1913 onwards, Renoir, who was very weak, could see little and had lost the use of his hands, entrusted the creation of the sculptures he imagined to the young artist Richard Guino, on the recommendation of the art dealer Ambroise Vollard. Guino, considered by Maillol to be his best pupil, was to be Renoir's "hands", transposing the painter's vision into matter with great accuracy. As early as 1947, art historian Paul Haesaerts wrote in Renoir sculpteur: "Guino was never simply an actor reading a text or a musician mechanically interpreting a score [...]. Guino was involved body and soul in the creative act. We can even say with certainty that if it hadn't been for him, Renoir's sculptures would never have seen the light of day. Guino was indispensable.

In 1965, Michel initiated legal proceedings on his father's behalf, seeking to have Richard Guino recognized as co-author of Renoir's sculptures. He obtained this recognition in 1971, which was confirmed by the French Supreme Court in 1973.

In 1977, an exhibition paid tribute to the collaboration between Richard Guino and Auguste Renoir at Les Collettes, the painter's final home in Cagnes-sur-Mer.

In the years that followed, until 1983, Michel Guino traveled extensively between New York and Morocco to work and, above all, to defend his father's work.

Michel Guino at the opening of the Richard Guino exhibition at Les Collettes, Renoir's home, in 1977.

In 1983, Michel Guino moved to L'Ormois in the Loiret region, where he bought the house of the painter Vallotton. He remained there until 2005, when he moved to Lancieux in Brittany, to be with his daughter Ariane and his grandchildren. Michel Guino died there on September 5, 2013, a few days before his 88th birthday.

What's striking about Guino's work, despite the plurality of his research paths, is the unity of style he maintains throughout: verticality, a subtle balance between strength and lightness, elegance and dislocation. Michel Guino is above all a poet of form who has made light his ally: "I put myself in front of bits of matter and materials, I question them and I make them dance", he used to say.

In 2004, an exhibition at the Bouquinerie de l'Institut in Paris showcased old and new pieces, providing a delightful opportunity to rediscover the power of Michel Guino's work.