Matisse was born in northern France, a region with a long textile tradition. He was born in Cateau-Cambrésis on December 31, 1869. After studying law, he worked as a solicitor’s clerk. In 1890, convalescing after an appendicitis operation, his mother gave him a box of paints. This episode determined the radical change of direction in his career. The following year, he gave up law to devote himself to painting. He moved to Paris and enrolled in William Bouguereau’s studio at the Académie Julian, which he soon left to attend the École des Beaux-Arts. He failed the entrance exam. The painter Gustave Moreau accepted him as a free student in his studio, often referred to as the cradle of Fauvist painting. Matisse met Henri Évenepoël, Henri Manguin, Albert Marquet and Georges Rouault. His daughter Marguerite was born in 1894. The following year, Matisse was officially admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in Gustave Moreau’s studio. From 1895 to 1897, he spent every summer in Brittany, at Belle-île-en-Mer. His palette gained in color and light. He married Amélie Parayre in 1898. The newlyweds went to London on their honeymoon, where Matisse discovered Turner’s paintings, before spending several months in Corsica and Toulouse. Ajaccio produced in him a “great wonderment for the South”: the generous vegetation, the light and the colors. His painting was enriched by warmer tones. Paul Signac’s Essay, D’Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme, published in 1898, undoubtedly encouraged him to practice the division of the brushstroke.

His son Jean was born in January 1899. When he returned to Paris, Gustave Moreau had died. His replacement at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Ferdinand Cormon, invited him to leave the studio. Matisse then enrolled in various academies: Julian, Colarossi, Camillo. At the latter, where Eugène Carrière came to correct, he met André Derain. He also studied with Antoine Bourdelle at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, but soon preferred the municipal school on rue Etienne-Marcel. There, he undertook Jaguar devouring a hare after Barye.

Birth of Pierre, his second son, in June 1900. Matisse creates his first drypoint etching, Autoportrait gravant.

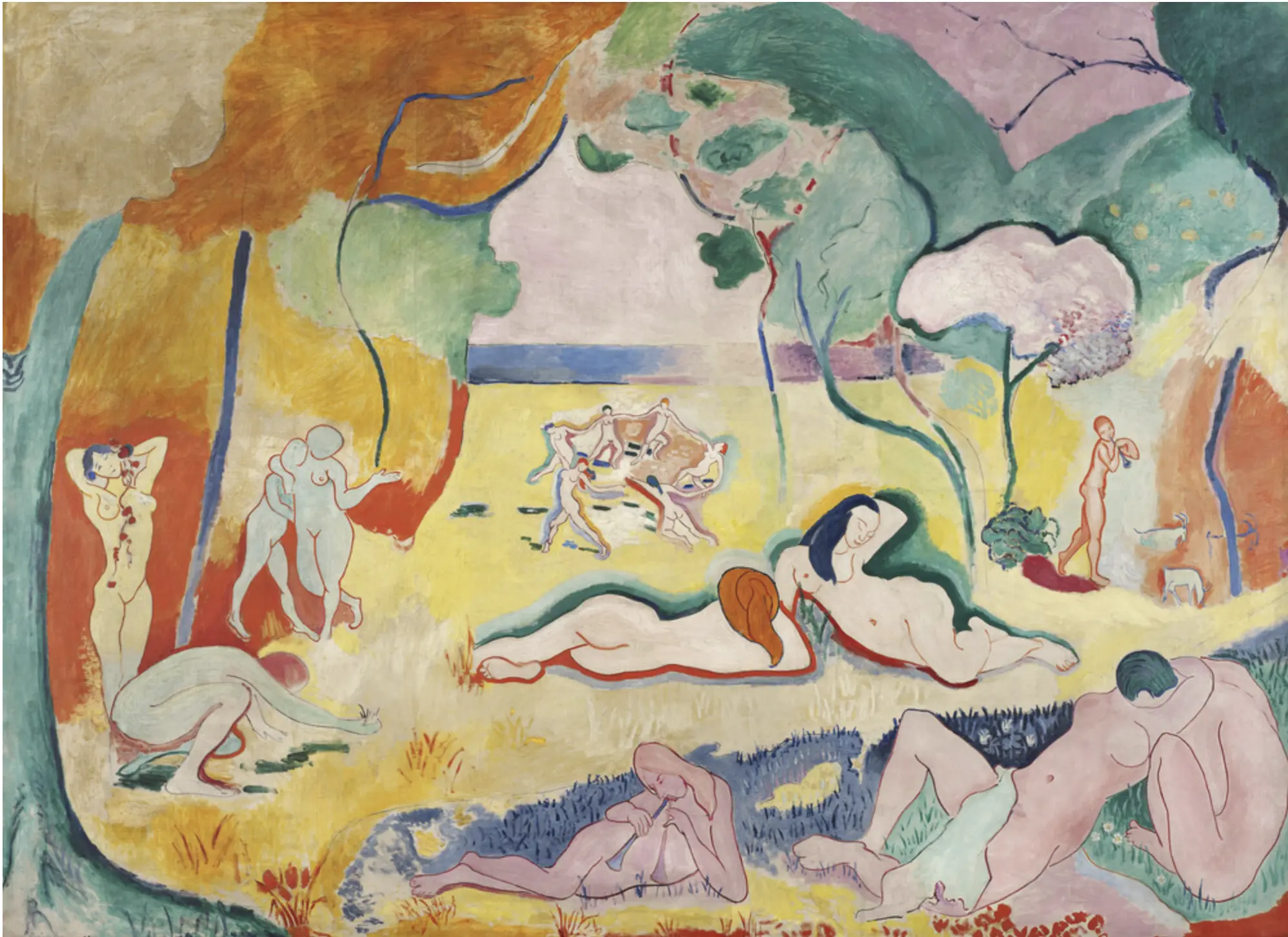

In May 1901, he returned to his family in Bohain, where living conditions were less difficult. From 1904 onwards, his situation improved. In June, Ambroise Vollard organizes the first exhibition devoted entirely to his work. He spent the summer in Saint-Tropez with Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross; Matisse tried his hand at neo-impressionist principles. In this style, he painted the famous Luxe, calme et volupté (Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’Art moderne, Paris, on deposit at the Musée d’Orsay), exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in spring 1905 and bought by Signac. In the summer of 1905, the artist stayed in Collioure, where he was joined by Derain. Stimulated by the intensity of the light, they exacerbated their colors, which they compared to “dynamite cartridges”. They present some of their summer creations at the Salon d’Automne, in the famous Room VII, named “cage aux fauves” by critic Louis Vauxcelles, which gives its name to Fauvism. Matisse paints Le Bonheur de vivre (Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania), presented in the spring at the Salon des Indépendants, and immediately bought by Gertrude Stein and her brother Léo. Until 1914, their home on rue de Fleurus was an essential meeting place for avant-garde artists. Matisse and Picasso met there in 1906. Picasso’s discovery of Le

Henri Matisse. Le Bonheur de vivre, between October 1905 and March 1906, Oil on canvas, final proof, 1946

(The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, USA)

The following year, he moved to 33 boulevard des Invalides. Spurred on by young admirers, he set up an academy. A significant body of work – thirty paintings, numerous sculptures and drawings – was exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in 1908. His work began to enjoy more international visibility: Alfred Stieglitz exhibited it in New York at his gallery 291; Paul Cassirer in Berlin. Matisse receives his first commissions from Russian collector Sergei Shchukin, including a decoration for his dining room: La Desserte rouge (Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg). Shchukin was a central figure in Matisse’s work. His commissions contributed to the shift in his aesthetic from easel painting to decorative painting. In December, Matisse publishes “Notes d’un peintre” in La Grande Revue, setting out the principles of his art. The following year, Chtchoukine commissioned a large-scale decoration for the staircase of his Moscow home. For the project, Matisse moved to Issy-les-Moulineaux, where he set up a large studio. He produced the bas-relief Dos I (followed by Dos II in 1913; Dos III in 1916-1917; and Dos IV in 1930).

In September 1909, he signed his first contract with the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris, which devoted a retrospective to him the following year. The large-scale decorations for Shchukin La Danse and La Musique caused a scandal at the Salon d’Automne in 1910. Together with Hans Purrmann, Matisse visits the great exhibition of Muslim art in Munich, which confirms his interest in Islamic art. In November, he travels to Spain (Granada, the Alhambra, Cordoba and Seville) until the end of January 1911. 1911 is a great painting year for Matisse. It saw the birth of his “symphonic interiors”, as Alfred H. Barr put it. Barr’s “symphonic interiors” – L’Atelier rose (Pushkin, Moscow), L’Atelier rouge (MoMA, New York), La Famille du peintre (Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) and Intérieur aux eggplants (Musée de Grenoble) – were born. He made a trip to Morocco, to Tangiers in late January-April 1912, followed by a second one after the summer, from late October to mid-February 1913. Paintings from this trip were exhibited at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery the same year. This marked the beginning of Matisse’s “experimental” period, which lasted until 1917.

The years 1916-1917 saw Matisse settle in Nice, a period of transition towards the painting of “odalisques”, often seen as a step backwards from the experimental dimension of his painting since 1905-1906. For Matisse, odalisques were in fact another way of responding to the problems posed by painting, notably the relationship between figure and background.

L’Atelier Rose, Pink Studio, 1911

Oil on canvas, 180 × 220 cm (Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow)

In early 1918, Paul Guillaume presented the first “Matisse Picasso” exhibition at his newly opened gallery at 108 rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, featuring some fifteen recent works by each artist. The two artists were to be reunited on several subsequent occasions. Almost ten years after his own discovery of Serge de Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Matisse creates the sets and costumes for the company’s ballet Le Chant du Rossignol, choreographed by Léonide Massine and with music by Igor Stravinsky. It premiered in Paris in early February 1920. In the autumn, in Nice, Matisse begins to work after Henriette Darricarrère, who becomes his favorite model for the rest of the decade. The artist publishes Henri Matisse, Cinquante dessins, with a preface by Charles Vildrac. The same year sees the publication of the first monograph devoted to his work by Marcel Sembat, the socialist MP and great admirer and collector of Matisse’s works. In 1923, Marguerite married the Byzantinist Georges Duthuit, who was to develop an original conception of Matisse’s work based on an aesthetic of the decorative in relation to oriental art. In 1925, Matisse began the

During the years 1928-1929, Matisse went through a severe crisis in his painting following the departure of Henriette, his model for seven years. He found it difficult to regain his inspiration. Faced with the canvas, he felt devoid of ideas. What’s more, from the outside, critics and other commentators were constantly re-evaluating his production in the light of his audacious works prior to the odalisques period. This constituted an additional form of pressure. In printmaking, on the other hand, he was very active, especially in 1929. The stalemate in his painting prompted him to seek out the quality of light in the other hemisphere. Matisse chose Tahiti. The interruption of this trip – from the end of February to the end of July 1930 – with a stopover in New York, followed by the commission for a large-scale decoration for the Barnes Foundation in the United States, helped to kick-start a new beginning.

In 1931, at the same time as working on the decoration for Albert Barnes, he executed the etchings for the illustration of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Poésies published by Albert Skira the following year, just after Ovid’s Métamorphoses illustrated by Picasso. In the summer, a major exhibition at Galerie Georges Petit revealed the odalisques to the public for the first time. In autumn, Alfred H. Barr, the director of MoMA, organized the most ambitious retrospective ever of Matisse’s work, and published a translation of “Notes d’un peintre” in the catalog, definitively introducing Matisse to the American art scene. It was both the first retrospective of Matisse’s work in the United States and MoMA’s first exhibition. 1931 also saw the opening of the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York, which played a decisive role in introducing not only his father’s work to the United States, but also the great founding artists of modernism (Georges Rouault, Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy, Alberto Giacometti, Jean Dubuffet, etc.). In 1932, an error in dimensions forced Matisse to undertake a new version of La Danse for Albert Barnes. This work kept him busy throughout the year. He hired an assistant, Lydia Delectorskaya, who became his model from 1934 onwards. She featured in major paintings of the period, such as Le Rêve (Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne/CCI, Paris) and Grand Nu Couché (Nu Rose) at the Baltimore Museum of Art, which marked the artist’s return to the bold painting that preceded his odalisques.

He travels to Merion in May 1933 for the installation of La Danse at the Barnes Foundation. On his return, he completed the incorrectly dimensioned version of the decoration, acquired by the city of Paris in January 1937 and named La Danse de Paris (Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris). During these years, Matisse multiplied his decorative projects. In 1935, through his son Pierre, he met Marie Cuttoli, who was looking for new models to revive tapestry production in the Aubusson workshops. He produced a cardboard window in Tahiti, followed by a second with solid colors to facilitate transposition into tapestry. The following year, he agreed to design the sets, costumes and stage curtain for Leonide Massine’s ballet L’Étrange Farandole(Rouge et Noir), set to Shostakovich’s first symphony. For the set, he uses the principle of the large arches of

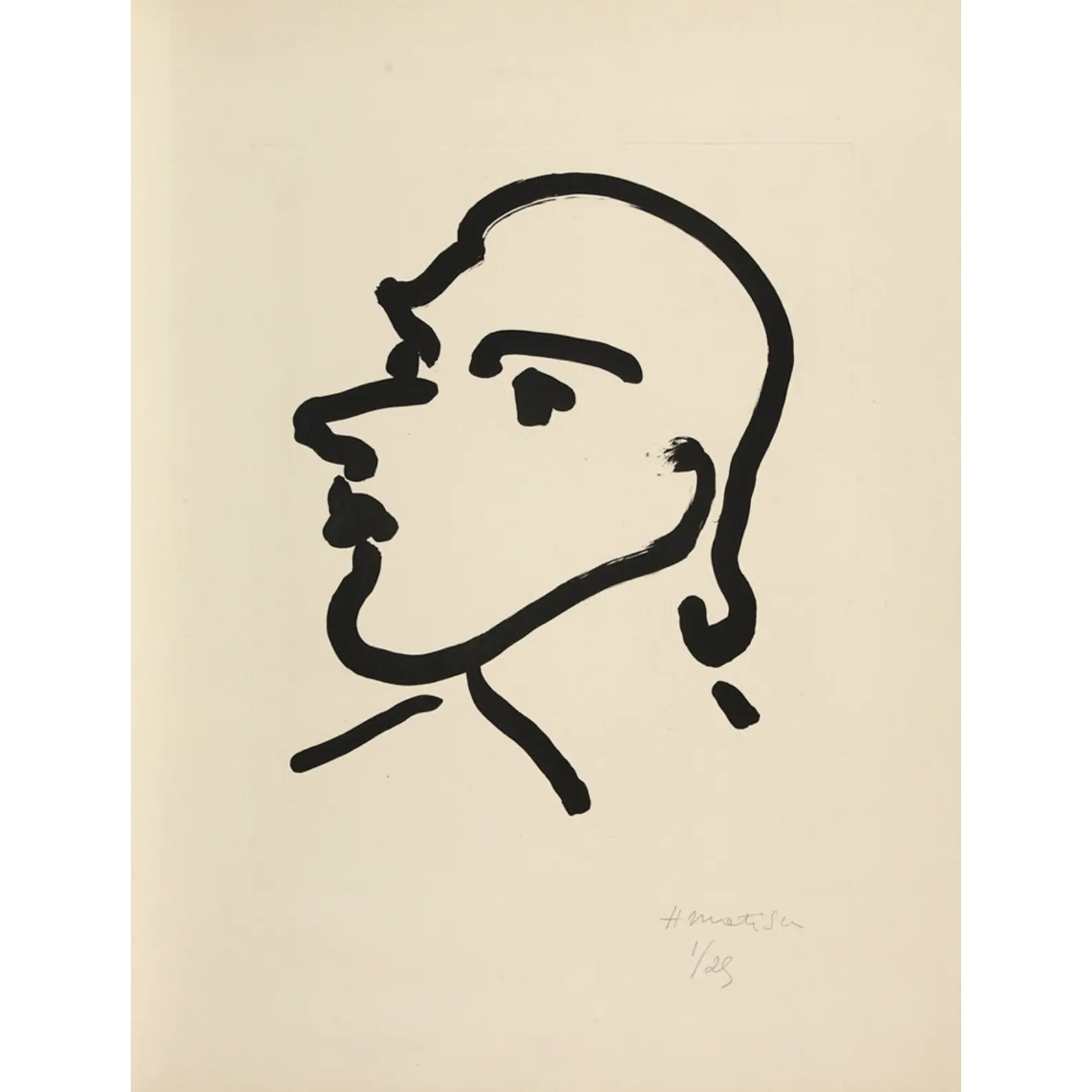

Henri Matisse, Nadia de profil, 1948, Original aquatint in black on Marai paper

In January 1938, in the former Hotel Excelsior-Régina in Nice’s Cimiez district, he bought two adjoining apartments, which he joined together. This was his last home-studio. Matisse’s second major text, “Notes d’un peintre sur son dessin”, is published in July 1939 in the magazine

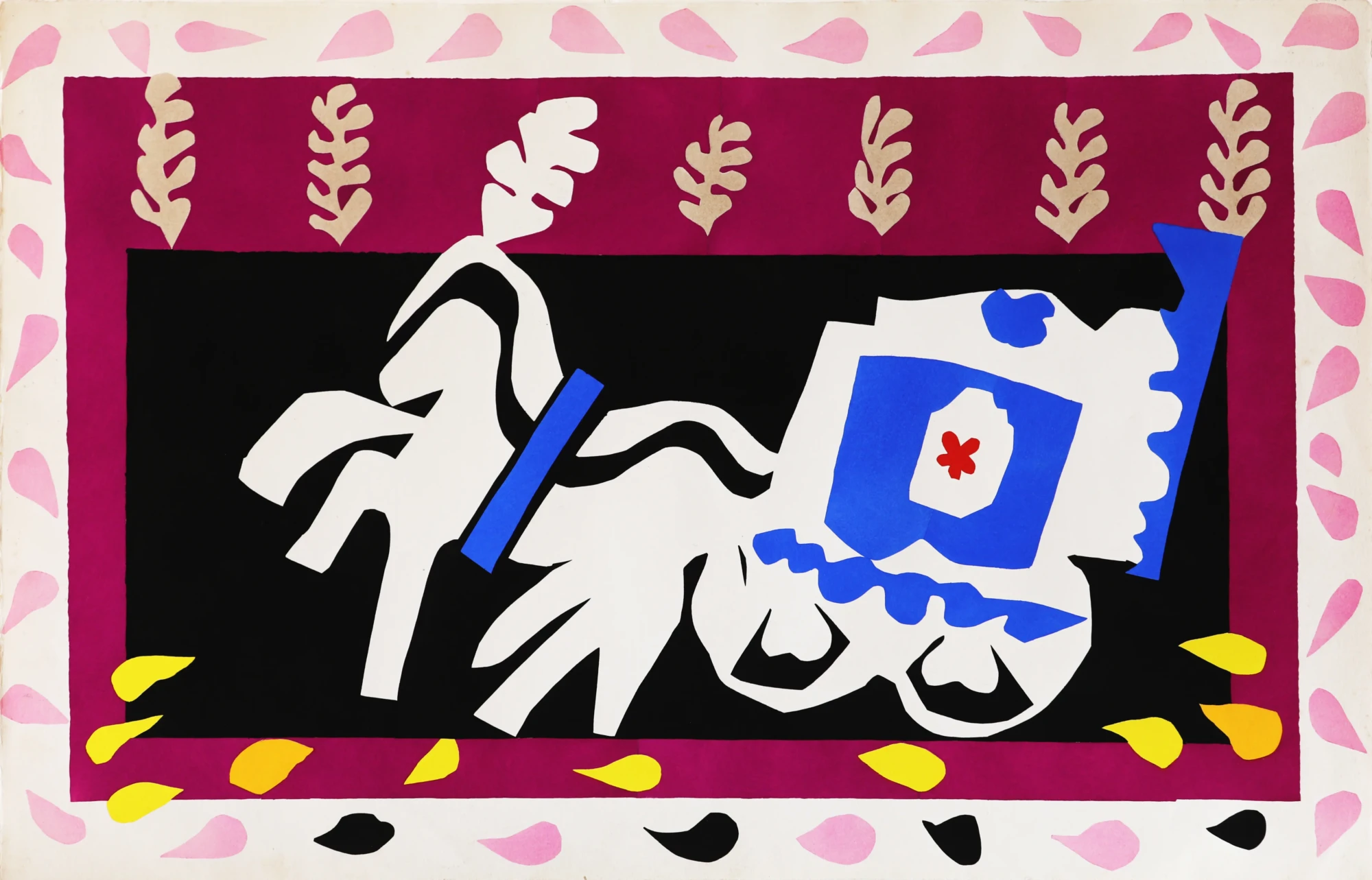

When it was published at the end of 1947, Jazz was enthusiastically received by the public. The following year, Matisse undertook the decoration of the Chapelle du Rosaire at the Dominicaines de Vence. At the time, religious art was undergoing a revival led by Father Marie-Alain Couturier. In the Vence chapel, two walls of stained glass dialogue with three brush and ink drawings on ceramic panels : Saint Dominique, La Vierge à l’Enfant and a Chemin de Croix. Matisse called the Chapelle “his masterpiece”. Following the success of the Philadelphia Museum retrospective in spring 1948, Pierre Matisse presented his father’s last works in his gallery in February 1949. Paintings and large-scale brush drawings in Indian ink shared the gallery walls with cut-out gouaches from the same period. During the summer, the exhibition was presented at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, with the addition of illustrated books, Oceania hangings and Polynesian tapestries, under the title Henri Matisse. Recent works 1947-1948 . The last years of his career were devoted to large-scale cut-out gouaches and brush drawings in Indian ink, such as the great Acrobates of 1952. After the chapelle de Vence, inaugurated in June 1951, Matisse increasingly turned to the creation of large-scale environments, such as La Perruche et la sirène (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam) and La Piscine (MoMA, New York), which chronologically frame the series of blue nudes. At the same time, through the intermediary of his son Pierre, he received commissions from America for stained-glass windows and ceramics, for which he composed cut-out gouache models. This last part of his work was revealed after his death in Verve‘s double volume, “Henri Matisse. Les dernières années 1950-1954”, published in 1958 (n°35-36), for which he designed the cover – the famous orange cover – and layout in 1954.

Matisse died in Nice on November 3, 1954. He is buried in the Cimiez cemetery.

Enterrement de Pierrot, in Jazz, stencil after collages and cut-outs by Henri Matisse, 1946

Matisse engraver

Matisse is the author of a substantial body of prints, comprising both independent etchings and illustrative engravings. His engraving work covers several processes – drypoint, etching, woodcut, lithography, linocut, aquatint – and unfolds in periods until 1941. He began etching at the turn of the century, in 1900-1903 – his first etching, Autoportrait gravant, was a drypoint in 1900 – then in 1913-1914, and again between 1922 and 1929. The twenties were a peak in the artist’s lithographic output, with works such as

Engraving has several statuses in Matisse’s work. It is a field for experimentation and research; an extension of his drawing; a complement to his other means of expression. Matisse frequently switched from one process to another, particularly when he reached a creative impasse. He then pursued his research in another technique.

The catalog raisonné of illustrated works comprises 139 issues. Of these, ten are illustrated books in the Matissian sense of the term – one could also say decorated books, according to the expression suggested by Raymond Escholier and approved by the artist.[1]. In other words, Matisse made a distinction between works in which he collaborated with one or more engravings without any further involvement, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses (1935), and those he composed entirely himself, which he more readily referred to as “his” books. For the most part, they were executed in a very short space of time, between 1941 and 1948. The illustration of Stéphane Mallarmé’s

The artist entrusted his daughter Marguerite Duthuit-Matisse with the task of supervising the printing of his etchings and the production of his books. In this task, Marguerite had the same exacting standards as her father. Claude Duthuit, the artist’s son and grandson, author of the catalog raisonné, relates Rouault’s remark on this subject: “There’s only one person more difficult than me with printers, and that’s Matisse’s daughter.[2] “.

Anne Coron, Doctor in History of Contemporary Art

Galerie de l’Institut

[1] Remarks by Henri Matisse reported by Raymond Escholier in R. Escholier, Matisse ce vivant, Paris, Arthème Fayard, 1956. Quoted in Dominique Fourcade (ed.), Henri Matisse. Writings and Proposals on Art Paris, Hermann, 1972, p. 214.

[2] Claude Duthuit, Henri Matisse. Catalog raisonné of the engraved works 2 vols, Paris, Claude Duthuit éditeur, 1983, p. XI.